THE EMPATHY TRAP – Why Future Leaders Will Need More

Originally published in German

THE EMPATHY TRAP – Why Future Leaders Will Need More

Mark has been captain of the MS Europa for 40 years. He is now handing over the helm to his successor. A young colleague who is highly regarded, very competent and equally likeable. Nevertheless, for the experts in the circle, he does not yet match Mark’s empathy.

On the occasion of Mark’s 60th birthday, he is described as “a phenomenal leadership figure”. They say he’s “deeply empathetic, always attuned to the feelings of his employees, quick to lend a sympathetic ear, and skilled at understanding guests’ perspectives”. His empathy is consistently highlighted as his signature strength.

When the comparison is made to his esteemed successor, my question abruptly silences the hymns of praise in the room: “Affective or cognitive empathy?” I ask.

I want to understand whether the 40 years of experience—with thousands of conversations and interactions with individuals of various backgrounds, ages, and value systems—have molded him to act ‘right’ in varying scenarios. Or is the secret behind his revered demeanor and leadership approach truly a profound emotional aptitude for empathy?

AGAINST EMPATHY

There’s something that’s been bothering me. Ever since I read the renowned psychologist Paul Bloom’s 2016 book, “Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion,” I’ve been contemplating the role of empathy in leadership.

When the “Harvard Business Manager” trumpeted “This is how leadership works” on the cover page this month and presented ’empathy’ as the most important leadership skill, I found myself revisiting my thoughts on the definition and role of empathy in leadership. Intuitively, many of us, including myself, would assert that empathy is of great significance.

Let’s be clear: I believe empathy is crucial. However, the question that intrigues me is whether empathy, in reality, stands as the vital strength that modern leaders need. Could it, in certain scenarios, turn into a hindrance? This is not only in the managerial realm but more broadly in our quest for a “better” life.

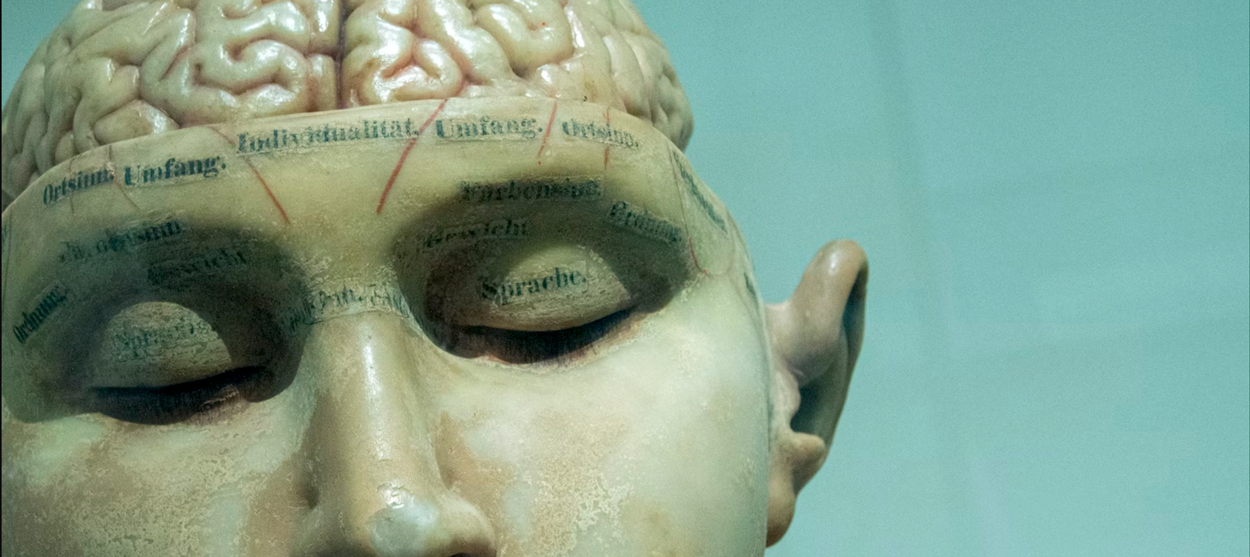

But how do we define empathy? What characterizes “empathetic leadership” for us? How do each of us interpret “empathy”? Its etymology, like the word ‘sympathy’, traces back to the Greek “pathos,” implying feeling and emotions. Bloom characterizes empathy as a spotlight with a narrow focus. It suggests that one can genuinely empathize with only one individual at a time. At best, one might juggle the emotions associated with two distinct situations or people, but three? The US author, Annie Dillard, found the mere idea so absurd that she remarked ironically: “There are 1,412,000,000 people in China. To get a sense of what that means, simply take yourself – in all your uniqueness, importance, complexity and love – and multiply by 1,412,000,000. See?” Nothing to it.

Empathy often emerges from an intuitive, emotion-driven “gut feeling” about a given situation. This does not guarantee that, as an individual, I am making the best long-term decision. Nor does it ensure that my empathy will necessarily have a universally positive impact. Especially in a business context, if our goal is mutual understanding – friendly interaction and progress (or improvement) – it becomes clear that empathy is not synonymous with kindness.

It’s a misconception to think empathy inherently leads to kind actions. Empathy, in fact, needs to merge with pre-existing kindness. It amplifies the reactions of those who already possess certain traits. Empathy makes good people better, because kind people do not like suffering, and empathy makes this suffering more apparent. Conversely, if a sadist were to become more empathetic, it might only increase their enjoyment in causing pain. For someone indifferent to another’s suffering, that pain becomes just an annoyance, and no positive action ensues.

And isn’t positive action the basis for leadership – or good leadership – as HBM writes? Peter F. Drucker once distinguished between management (“doing things right”) and leadership (“doing the right things”): It’s about ‘doing the right thing’. The foundation of business, leadership, and entrepreneurship is progress – specifically, positive progress. This is where rationality becomes crucial. However, this presents the dilemma that emotions and empathy don’t inherently drive rational action.

Consider this: If a newspaper reports a tragedy claiming 200 lives today, and tomorrow revises the count to 2000, do our emotions intensify tenfold? Do they amplify at all? It’s doubtful.

In fact, the fate of an individual can elicit more feelings than that of two hundred, because individuals can elicit feelings in a variety of ways: We identify with individuals. In his book, Bloom mentions two apt quotes here. Stalin reportedly once remarked, “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths are a statistic.” Similarly, Mother Teresa purportedly observed, “If I look at the masses, I will never act. If I look at one, I will.”

It’s only through reason, rather than emotion, that we can grasp the moral significance of larger numbers. And that brings us to the core of Bloom’s argument. He posits that empathy, due to its inherently biased and narrow focus, fails as a reliable moral compass. It lacks nuance and proportionality. Further, Bloom emphasizes the emotional toll empathy can exact on the individual, a phenomenon termed ‘unmitigated communion’. It entails resonating so deeply with another’s suffering that it becomes a personal stressor. This overwhelming empathy has been recognized as a precursor to “burnout” since the 1970s and finds resonances from scientific circles to Buddhist theology.

Matthieu Ricard, renowned both as a Buddhist monk and neuroscientist, delves into this concept. Drawing from Buddhist scriptures, he differentiates between “sentimental compassion” and “great compassion.” The former aligns with the conception of ’empathy’ as discussed in this article, while the latter can be succinctly termed as “compassion.” Ricard warns against the draining nature of sentimental compassion, which, he suggests, “exhausts the bodhisattva.”

This perspective ties back into the core philosophy of the Bodhisattva: to aid all beings in achieving liberation from the cycle of reincarnation (samsara) before oneself. It is the sustainable, detached nature of great compassion that is deemed the ideal.

Recent advances in neuroscience echo these ancient teachings. Research by scientists like Tania Singer and Olga Klimecki illustrates that “great compassion” doesn’t involve mirroring another’s distress. Instead, it manifests as warmth, concern, and a genuine desire to enhance the well-being of others. In essence, compassion means feeling for someone, rather than immersing oneself in their emotions. This distinction is supported by fMRI studies that differentiate between the neural signatures of “human warmth” and “exhaustion.

LIBERATING FROM OUTDATED CERTITUDES

At the heart of modern leadership challenges, we must ask: Is the core problem in business a lack of feeling or is it more about discerning and taking the right actions? And if it’s about actions, does empathy necessarily propel them?

We live in a world and a time when we are trapped in (old) certitudes, and use absolutes and terms without really being clear ourselves what we mean. We toss around terms like ‘digital transformation’ without truly pondering what we aim to transform into. We seek a ‘purpose’ without fully grasping concepts of meaning, meaningfulness, or the journey to discover that meaning. Everything is neatly packaged, categorized, sold, communicated, and reacted upon, yet genuine reflection appears to be dwindling.

I concur that empathy is invaluable in leadership. It fosters connections, enhances communication, and establishes trust. But is empathy alone sufficient? Or, more pointedly: Is there a point where empathy might become a liability in leadership?

Bloom contends that our traditional interpretation of empathy can result in biased choices, favoring those we naturally resonate with or those already close to us. In doing so, we might overlook a more comprehensive and objective perspective. Such is the inherent bias of empathy.

The suffering of one’s own child causes more pain than the suffering of a distant child. We instinctively prioritize our loved ones, sometimes even making seemingly irrational choices, like saving an ailing mother over her three healthy children. Given this, when considering professions like emergency doctors who operate on tight schedules, should we be emphasizing the diversity of feeling and increased empathy, or should the focus be on timely and appropriate action?

Improvement and progress often stem from deliberate, rational actions grounded in experience. Contemporary psychology encapsulates this as: “Empathy is the initial step towards compassion.” Only by recognizing and empathizing with another’s suffering can one progress to feeling compassion for them and subsequently taking action. But is this the kind of action required of a leader aiming to propel a company and its workforce forward?

THE RATIONAL LEADER: EMBRACING COMPASSION

The crux of our inquiry isn’t merely about how we individually interpret empathy, but more about its utility. Does “empathetic leadership” inherently drive us towards any given goal? If empathy is touted as the paramount leadership attribute, then it inherently implies motivation – leadership in action – followed by its consequence: progress.

Effective leadership should by definition guide us towards positive progress. This could manifest in broader societal benefits such as enhanced community and social cohesion or on a more personal level, alleviating suffering or fostering individual growth.

Thus, we return to the central inquiry: Does empathy activate? How does empathy contribute to a “better world”? And what, precisely, do we mean by a “better world”? Answering these questions demands a foundation of assumptions. These assumptions then lead to an opinion about something. In turn, however, this is based on rational considerations.

Bloom advocates “rational compassion” – a nuanced approach interweaving comprehension with evidence-based decision-making.. This form of compassion is not influenced by the immediate emotional flood. Instead, it weighs long-term outcomes, thinks critically about the broader implications, and acts based on what will lead to the best overall outcome.

Which would bring us back to Captain Mark. He is an ‘action hero’. It’s not his feelings that make him heroic, but his actions. One might even argue that his feelings don’t matter as long as the recipient feels that he empathizes – the essential thing remains the action. At this point, we can counter that a feeling – empathy – would be required to get to the action, but such an anthropomorphization becomes obsolete at the latest when a deeper understanding of cognition and current technology development comes into play.

This aligns with my distinction between “affective” and “cognitive” empathy. Throughout my interactions, many have recognized my empathetic vigor. A comment on LinkedIn about a new HBM issue read, “Anders Indset has long championed empathy in leadership.” True, while I deeply value feelings, for me, it boils down to a profound understanding of progress.

Affective empathy is inherently emotional, whereas cognitive empathy blends analytical insight with experience. Here, data and analytical prowess dictate responses. Hence, Captain Mark’s actions could stem from accumulated experiences and multifaceted intelligence, like social competence, enabling him to project emotional empathy.

In our era of burgeoning artificial intelligence, coupled with real-time analysis via camera and voice recognition, machines can discern human feelings and thoughts with precision. Group dynamics can now be technologically evaluated. It stands to reason that future machines or robots might evolve into consummate cognitive empathizers. Could AI, devoid of emotional biases and equipped with the capability to interpret body language, facial cues, and vocal tones, be primed for making rational, compassionate decisions? If so, we must delve deeper.

This brings me to my pivotal argument. Given the wealth of data and research at our disposal, do our feelings truly mold us into superior leaders? Would we act more ethically based on raw emotion or through a comprehensive grasp of immediate and prolonged, individual, and collective ramifications? Perhaps a society filled with emotionally-charged individuals isn’t our zenith.

I envision an educational philosophy that instills both empathy and foresight in children and leaders. This would cultivate a society where individuals are intrinsically driven to do good, harmoniously blending heartfelt motivation with an astute understanding of their actions’ repercussions.

For me, such sagacious introspection underpins a truly enlightened society.

REDEFINING LEADERSHIP: FROM EMPATHY TO ACTION

The term “compassion” often takes me back to its English roots, which is interwoven with passion – passio –, implying suffering. However, in modern times, passion has evolved into a positive force, driving one towards something. Take ex-captain Mark, for instance. He channels his passion positively, acting for the betterment of his surroundings. Analyzing both immediate and future implications, he acts with rational fervor. Those at the receiving end of his actions perceive them as empathetic, acknowledging their feelings and needs. Here, rational compassion marries cognitive empathy, resulting in “right” action.

The leadership we know stands on the threshold of a fascinating development. As we continue to advance into this era of AI- and data-driven decision making, we may find that our long-held notions of leadership – so deeply rooted in empathy – need revaluation.

Leadership now pivots to discerning the emotions of employees and stakeholders, either through technological insights or cognitive abilities. It’s a balance between catering to immediate needs and aligning with the company’s long-term objectives. In essence, leadership is about decisive action.

But our actual – and crucial – question remains: Does empathy activate, or is it often more about re-enacting feelings? The cover of the current HBM issue is adorned with a heart, but what does it stand for?

Yet, the enduring question remains: Is it empathy that propels action, or is it just an imitation of feelings? While the heart symbolizing empathy has long been deemed the cornerstone of leadership, maybe it’s time for the mind—the rational, compassionate mind—to claim its rightful place at the forefront of effective leadership. Especially, as we navigate the currents of technological evolution, this mental acuity might just be the paramount leadership trait.

We have long considered empathy to be the beating heart of leadership. Perhaps it is time to recognize that the mind – the rational, compassionate mind – must play an equally decisive role in effective leadership. In the rapid time of progress and development, it is above all about activation. So perhaps the heart and empathy are not cover-worthy, but better our mind?

Don’t misunderstand; I advocate for a heightened sense of emotionality. But in leadership, particularly in the corporate realm, the focus shifts to “filling” – infusing conversations, dialogues, and scenarios with purpose and forward momentum. The primary onus of a leader? To catalyze positive progress. This necessitates cognitive empathy and, more importantly, rational compassion.

Understanding empathy, distinguishing between its affective and cognitive dimensions, and differentiating it from sympathy and compassion is intricate. But as the Dalai Lama, in his avatar as an “economic sage”, opines, “Capitalism is a working model, but it needs compassion”. It underscores the necessity for compassionate leadership, prompting reflections on what truly constitutes effective leadership, or in other words: “This is how leadership works”.