The Forgotten Potential – Why We Need to Art Right Now

– Reflecting on Powerful Prescience and Reshaping Posterity’s Future –

Bonn, December 17, 1770: the first artist is born. To be more precise, this is likely the date of his baptism; the actual birthdate remains unknown. With him—Ludwig van Beethoven—art is poised to take on a creative role. Beethoven, already gifted from birth, will ultimately commit himself to art without compromise.

Art is magic, delivered from the lie of being truth.

—Theodor W. Adorno

Beethoven found true freedom. Until this liberation, art was predominantly a function of techne (an ancient Greek term describing the European philosophy of art, science, and technology). It was without its modern wonder—skill sans soul. At least as far as public perception was concerned.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s passions and oratorios years before symbolized craft and commission, subject to the demands of the church and the routine of the church calendar. They were soundtracks for Sunday services, created in a manufactory. Lucas Cranach, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt van Rijn had already worked in a similar fashion—albeit with the visual arts. No work without a commission. Beethoven was the first to value expression over coinage. He didn’t allow himself to be hired, as he wanted to create. And for this reason, art underwent a metamorphosis like none other.

LEARNING TO THINK

Art represents the potential of thought, and creation becomes an expression of thought. When the thought emerges, art manifests the expression of an experience thereby conveyed. Thus, art finds its creative role in association with philosophy. Self-evident “things” are questioned for their functionality. As commentary, art becomes commentary.

In aesthetics, Hegel, among others, also found reference to the spiritual concern. Beyond expression, Hegel was primarily concerned with understanding. Over the course of the following two hundred years, artists were only posthumously recognized and understood for their works. Beethoven was the same. They lived “between the paradigms.”

ART IN TIMES OF TECHNOLOGICAL OMNISCIENCE

What is the role of art today? Has this creative potential been lost, or are we so caught up in our reactionism that we fail to recognize the artist as an enlightener?

Around 1970, art returned to a state of complaisance and economization. Pablo Picasso was invited to be honored at the Louvre on the occasion of his ninetieth birthday, the first artist to have a retrospective dedicated to him during his lifetime. Art was present and pleasing again. The creative aspect of art, however, is not the object, but the irritation, the awakening.

The perception, sharpened through art, triggers the thinking itself.

In the seventies, the artistic creations of Frida Kahlo were discovered as part of the women’s movement. Posthumously, works of art have become “greater” than they were understood to be in their time. Is that even possible today? Vivian Westwood, Madonna, or street art à la Banksy—art today strives to be understood in its time in order to please. It excites, but it doesn’t irritate. It generates emotions and has an effect, but it doesn’t shape. It is present but not “alive.” The like, the sale, the immediate confirmation of a collective opinion with an economic premium. This is how complaisance trapped in its time expresses itself: where art represents the new, it takes place within the boundaries of the present. Art is degraded to an aesthetic asset with the like-me potential for the decadent society.

Art, however, is the first closer interpreter of religious ideas, because the prosaic contemplation of the objective world asserts itself only when man, as a spiritual self-consciousness, has fought his way free of immediacy and faces it in this freedom, in which he understands objectivity as a mere externality.

—Hegel

To internalize this, we need an understanding of art beyond mere acquisition. Art itself can play a role (again). As a creative cultural product. In its absolute purity, it lives between time—between paradigms—and cannot be understood in its time.

Yet, it’s not inactivity but animation that constitutes its role: destructive, devoted creation.

THE ARTIST IN META-MODERNITY

So, how do we become artists? How can we, in the Hegelian sense, capture our thoughts with a temporal perspective of the past—of dealing with the self-evident—while, at the same time, understanding the world around us?

What does the artist do? He deals with the world. He deals with it in the form of individual expression. This is an artistic process of understanding. This is characterized by a balancing act between the world flooded with stimuli and the solitary existence, secluded from the world in the studio—in the mind. The artist needs the world flooded with stimuli, which he takes in with all his senses. Without this, no inspiration is so important for the artistic act. But he also needs the seclusion and silence of his studio. A life between vita activa and vita contemplativa—this is the artist’s way of life, but one in which he can never achieve an absolute balance, for expression is, itself, alive.

ART: THE CROWNING CREATION

Understanding is a laborious process, which is connected with much frustration and suffering. But this is existentially important because only through this trial does the artist become someone. This is his happiness in life. While the artist’s art has rough edges and repulsive aspects . . . while it isn’t always easy to grasp—like life—what the people-pleasing artist produces is flat, without resistance, easy to digest, ultimately consumable and affirmative. The latter form of art doesn’t cause a stir and thus offers no potential for friction that invites debate.

Flat art doesn’t want debate. It shies away from confrontation. In the end, it can’t facilitate as much either—because it is nothing. It lacks substance. How can it be if it is continuously emptied by the artist? Nothing has built up in it. Nothing has developed. Through it, nothing was created. This art isn’t the result of a creative process. It is, as it were, nihilistic. It wants to be heard. It wants attention. That is its aspiration. It exploits the world for its own generation of attention. There is an instrumental relationship between commodity art and the world. This distinguishes art as a commodity from true art.

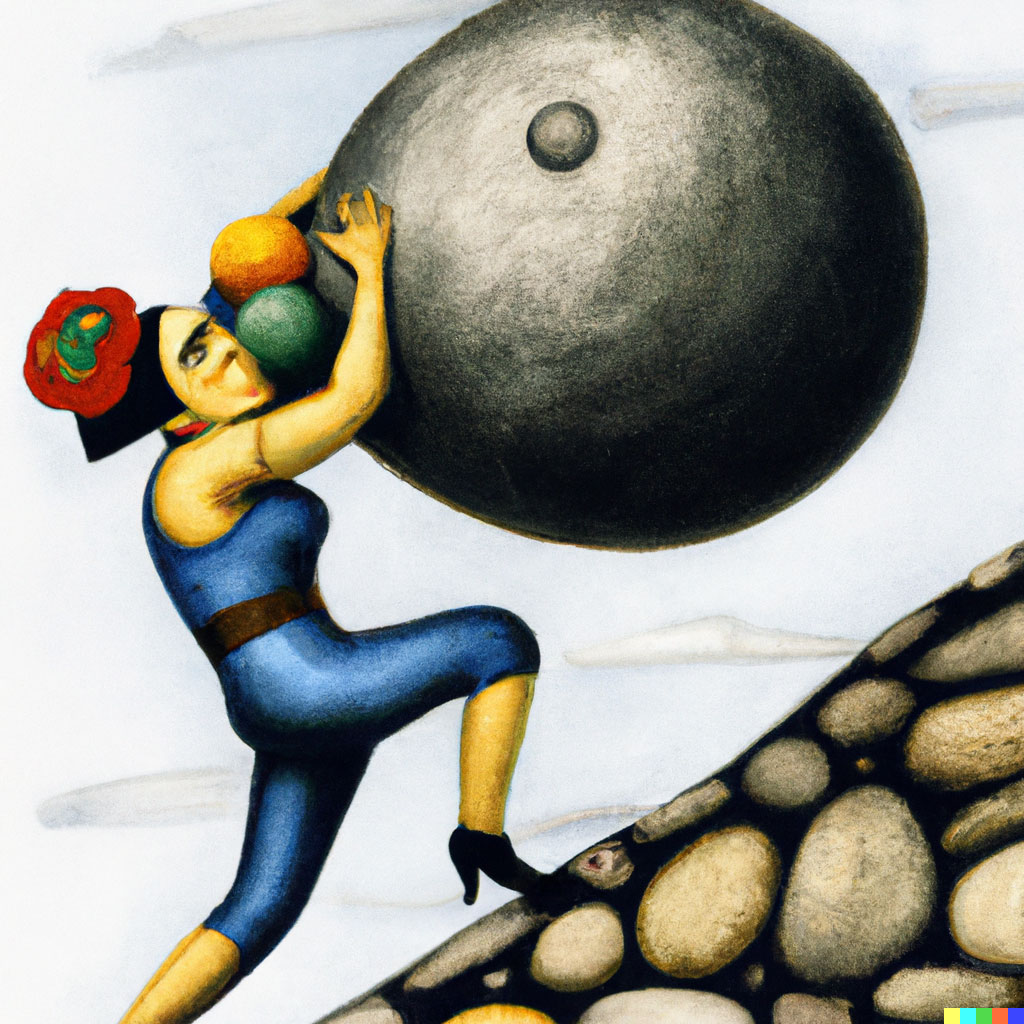

The latter is driven by a destructive creation. It takes apart the existing and creates something completely new and strange out of it. But the new is only a moment, which is why this moment is again transcended by the artist through his artistic undertaking. Perhaps as a culmination of this creation, Salvatore Garau auctioned his “invisible sculpture” for $18,300. Art literally made from nothing. “It is a work that asks you to activate the power of imagination,” said the Italian artist. Consequently, the artistic act is the consummation of reality. Art is temporality, while the commodity of art remains arrested in the totality of the present. If the world is a representation of the human imagination, Garau’s work is the culmination of creation.

GOOSEBUMPS ARE HARD TO “GOOSE AWAY”

But if we need expression, art needs a reaction—goosebumps. Likes may unlock a few endorphins, but they certainly don’t create goosebumps. As art has been atomized into the “anything goes” of social arbitrariness, it has lost the ability to irritate—the creative power to shape. Perhaps a self-optimizing society can only be irritated by questioning its absolutes, which are reflected in a penchant for the measurable—even in art where uniqueness has recently manifested itself in blockchain-based NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens).

With complaisance, art is also losing its questioning component. While engineering is needed for implementation, psychology, philosophy, and art are needed for design. The field of psychology is said to have sprung from philosophy (as the “doctrine of the soul”) and thus bolsters creativity. However, I’m convinced that technological development is tending—although some will certainly disagree with me—toward the measurable, consequently towards a fusion with the neurosciences. Psychoanalysis and psychology have thus landed in the technological-scientific realm. What is perceived and felt can increasingly be measured—all the way down to how and when neurons fire. In the merging of psychology and psychoanalysis with the neuroscientific field and the crisis of philosophy, it is art that must supplement engineering in a “magic triangle.” Should we fail to uphold art, we soon shall be reduced to pure science in a ‘Final Narcissistic Injury of Mankind’—the technologically divine creation of ‘Homo Hbsoletus’.

What is needed are people who understand people—cultural engineers, so to speak. The cultural engineer also takes on a role as a companion in design and on the path to healing.

An artistic revival is now needed more than ever before. Today, it represents a humanistic approach to a fractured future. If it isn’t fulfilled soon, philosophy will be left behind, and “likes” will supplant “true love.”

Let’s Art.